Reading and Deaf Children – personal experiences

Index

- Hilda Lewis – Everything has a name. A fictional account of how a young deaf child realises that objects have names

- Janice Silo – Thoughts on reading. Janice is herself deaf, and despite obstacles became a Teacher of the Deaf

- Ted Moore – Teaching reading to deaf children (circa 1971). Ted Moore is a former president of BATOD and a former head of Oxfordshire Sensory Support Service

- Linda Watson – Teaching literacy to deaf pupils in the 1970s – a personal account. Linda has been a Teacher of the Deaf, a senior lecturer in deaf education and, until recently, an editor of Deafness and Education International

- Ruth Swanwick – Sign bilingual education – reading and deaf pupils. Ruth is Professor in Deaf Education and Director of Research and Innovation for the School of Education, University of Leeds

- Mabel Hardie-Davis – Dickens Points the Way. Mabel Davis was a Teacher of the Deaf and for a long period the headmistress of a school for deaf children. She has been able to draw on her experience as someone who became deaf in childhood through meningitis.

Content

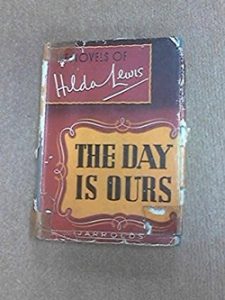

The first account by Hilda Lewis is unusual for this website as it is a fictional account. However, it describes very vividly how deaf children might come to realise the significance of the written word. ‘The day is ours’ is a novel written in 1947 and it was made into a film, ‘Mandy’ in 1953. The author, Hilda Lewis, was an established novelist whose novels covered a range of topics. Her interest in deaf children may have come through her husband, an academic, who published books concerned with the social and language development of deaf children.

The second account by Janice Silo reflects upon how she herself learnt to read. She argues very strongly that good spoken language is not essential to learning to read. Although she demonstrates how much can be learnt from deaf people themselves, she also describes the difficulty she had in getting training as a Teacher of the Deaf, even though she was already a qualified teacher.

Ted Moore and Linda Watson describe their own teaching experiences in the 1970s. Both talk of the limitations of the hearing aids available then. They also talk of how they came to realise that making stories meaningful and providing a context for reading was an important part of encouraging the development of reading skills.

Ruth Swanwick came to teaching deaf children from a modern foreign language background. She found the skills she had learnt there transferred to teaching deaf children who were being taught through a bilingual approach. She talks of the importance of pupils interrogating text and discovering patterns in written language.

In the sixth account, Mabel Davis describes her experiences in teaching reading as a person who became deaf through meningitis during childhood. She stresses the need for the teacher to have an open mind and take a flexible approach to reading in deaf children with an emphasis that focuses on the abilities of the child.

Tamsie is just beginning to learn that ‘words’ identified by some sound and lip patterns, had meanings.

She could speak. Her speech was at first halting, confined to the simplest, the most concrete facts; and the voice that sounded them, ugly. But in her deep happiness, in the blessedness of being able to communicate, she would not have changed places with any other child in the world. She could speak.

She could speak. And now she was beginning to read, to write.

Teacher took the doll in her hand. Doll, she said. She picked up a piece of chalk. ‘Doll’ she wrote. Tamsie looked. Something was stirring in her mind. For the first time the white marks on the blackboard might mean something.

Teacher held the doll next to the white marks. Teacher took the doll and put it down on the table, she pointed to the word on the board. Something clicked in Tamsie’s mind. She ran over to the table, brought the doll and held it against the white chalk marks. Suddenly, magically, the marks, unrelated, unknown, became a word.

Teacher took the doll. She put a piece of chalk into Tamsie’s hand. Tamsie looked at the word on the board and then, slowly, as one might make a drawing, copied it. Then bubbling with mirth, she made a child’s primitive sketch beside it – a circle for the head, a circle for the body, with two arms like pitchforks and two legs like rakes. D-O-L-L. Underneath the drawing she drew the word again, Suddenly, rapidly, she was covering the backboard. With slow care. Doll, Doll, Doll…

Teacher went to the cupboard and took out a ball. B.A.L.L. Tamsie’s lips shaped the well known movements. Teacher took a duster, cleaned the board and wrote Ball. Tamsie picked up a pen, a book, a pencil; as she sounded out the words, Teacher wrote them upon the board.

Now that she understood the significance of talking, of reading, of writing, she had a wild, a savage desire to learn. Within three months of the day Teacher had chalked doll upon the board, Tamsie was reading little sentences. She was being led, sometimes rebellious, step by difficult step.

Note: We have tried without success to get permission to use this material. Anyone holding the rights to this book should contact us via the website.

This is a messy ‘essay’ as it will be actually the first time I have really thought about reading wholly from my perspective!

I was asked if I could write about my reading experience. I was loathe to become vulnerable because as soon as people see the word ‘deafened’, their immediate reaction is ‘oh, its ok for her, she was born hearing and probably had the basic SVO (subject-verb-object) structure established well before she became deaf’. I have no idea if the basic SVO structure was there or even if I had that great an advantage over my peers. I do know that some of my peers who were born deaf had a better grasp of English than myself and their spoken language was often more easily understood than my own. The difference could have been that I wanted to experience life in a different way. I wanted eventually to go to university and become a teacher. Enlarging my basic SVO took many years of hard work and even today in my early 70s I can still sometimes reduce friends, deaf and hearing alike, into giggling fits with my weird English.

But let my story begin.

My experience of reading had not begun when I was on the cusp of being transformed from a hearing toddler to a totally deaf one. I became deaf through TB meningitis.

My background is this – I lived with my grandparents in the country until I was about 3-4. My only parent was then a single mother working in the city, earning a living to support both of us. As far as I remember, there were no books and I cannot recall newspapers in the home but I do remember the small radio. I don’t remember sounds or listening to it. When my aunt was old enough, she bought comics for me. The words I ignored but I enjoyed the pictures but this was later.

From the age of 4-5 years it was a blurred and traumatic time for all of us – my mother suddenly had a deaf child without any warning and my speech became unintelligible very quickly. Myself I wondered why no one understood me and why I felt I was in a fog for a long time afterwards.

At the age of 5 I started attending a hearing school but I was withdrawn by my mother because I was scolded and criticised for not paying attention and being rude. She was furious as I was smacked for that and I began to attend the local day deaf school. In this school I felt safe and welcomed.

Hearing aids (the old fashion body ones as well as the early post aurals) became the bane of my life as no one believed I could not hear with them although my teachers believed I was telling the truth. A few years later they were astonished when I declared I could hear something. I did not explain that I felt left out being the only one without a hearing aid in my peer group! So, for the last few years I had to wear hearing aids. I learned my lesson!

My reading began with Janet and John. Everything but signing was thrown at me at an attempt to encourage my reading skills. If I did not understand, objects were shown and my teachers attempted to make them meaningful although the use of middle class language was a block for a long time. Also, there was no sense of relevancy within this reading scheme for me. Of course, it wasn’t until I was in my late 20s that I realised the importance of accessible English with a sense of relevancy for the reader.

I have fond memories of a few of my teachers – Miss Henderson, Mrs. Davies and Mr. Wells. Miss Henderson in particular. Once she tried to help me to understand the word ‘knickers’. In the end, she showed me a tiny glimpse of her own pair which was pretty long down her legs and pointed to it and said ‘knickers’. I was a bit confused but got the gist of it! Their approach to reading was, I thought, after I qualified as a teacher, pragmatic, even humane if I can use that word. One of my contemporaries said to me only a few years ago that he could not lipread our teachers to save his life. It was true and we agreed that his use of English (reading) showed that at least their pragmatic approach worked for him but in a more limited way. We grinned at each other, both of us recalling our own particular struggles within the oral system. It gave him a foundation upon which to build whereas I probably thrived (again probably too strong a word) in this oral environment as regards to reading compared to him – yet we both had to work very hard to develop our English skills too.

As you can gather, the working philosophy at my school was oralism, but it was quite a laissez faire approach. I hated speech lessons because I could only speak as a deaf person. I had no hearing. It was soul destroying sometimes. I could do my best but my speech never seemed to be good enough. But I soon enjoyed reading as long as I didn’t have to endure many speech corrections as I went along. ‘Nonetheless`, I still left school feeling a failure because of this constant criticism of my speech.

One of the most important things I know is speech is not the key to reading. It may help some people but those without clear speech can and do learn to read regardless.

One of my cleverest students had no speech but went on to university. Education is not about learning to speak. It should be about absorbing knowledge. Alas for many deaf people of my generation, speech was the be all and end all of all education..

Note: Perhaps I should add that my own university declined to accept me as a trainee teacher of the deaf. In fact, only London accepted me. This was despite my qualifying as a teacher of hearing children, having a degree etc. My deafness still motivated them to reject my application to be trained as a Teacher of the Deaf

I have a book printed in 1809 in which a letter written by the Abbé de l’Epée says “Do not hope that they (deaf children) may ever be able to communicate their ideas by writing.”

Had times and thought moved on by the 1970s?

I transferred from teaching in a grammar school to working in a primary school for the deaf. My first class was with 9 and 10 year olds, all of whom had some hearing and speech and in those days were considered to be ‘partially hearing’. Quite a number of them had other learning difficulties too. As much use of headphones and a blackboard was made but there was no overhead projector, smart board, or radio aids available. Often, while I was writing on the blackboard the children were having a conversation in sign behind my back.

I hadn’t been there long when I came across some International Phonic Alphabet (IPA) Ladybird books hidden away in a cupboard and apparently abandoned. It seemed that the school had come to the same conclusion related to how you teach reading through phonics if the children can’t hear all sounds properly? In fact, how could you teach deaf children to learn anything?

So I muddled along, gradually gaining a degree of insight into what it means to be deaf. I found that by engaging in topics that the class were interested in, a foundation was laid for drawing up a script, reading it, asking questions, and getting responses in both spoken and written forms.

The spoken element could also be used for the teaching of speech! I later learnt that this approach ‘Listening, reading, speaking’ (LRS) was one that was beginning to be used around the country.

This also seemed closely linked to Father Van Uden’s approach in St. Michielsgestel (a school for the deaf in the Netherlands) called the Maternal Reflective Method (MRM) based on a whole child approach where learning in all aspects of life should be developed by focusing on the child ‘doing’ and discovering, through shared interaction, and particularly through conversation. This then led to using spoken language, reading, writing, pictures, objects, symbols or key signs throughout the day.

Shortly after this I also came upon ‘Guidelines’, an English Language Course by F.J. Thomas who worked at Woodford School for the Deaf. It was a very hierarchical course, beginning with very simple language forms and lots of repetition but evolving into complex sentence structures. It allowed for the development of language, reading, speech, and sequencing.

For example, Book 1 began with ‘What is that?’ and ‘That is a spider’

and book 18 ‘The teacher asked Paul, “What did Andrew do?” Paul answered, “He knocked at the door. He is a postman”.

So, communication development involving syntax, vocabulary/semantics, plurals, etc combined with articulation, was incorporated into the day’s teaching. Some will say: “Too stilted and artificial”. But it worked for many!

Bibliography:

‘Instruction for the Deaf & Dumb’ by Joseph Watson, L.L.D. (Printed and Sold by Darton & Harvey) 1809.

‘A World of Language for Deaf Children’ by Dr. A. van Uden. (Printed by Swets & Zeitlinger, Amsterdam and Lisse) 1970

My first job teaching deaf pupils was at Whitebrook School for the Deaf in Manchester, where I started teaching in 1973. Hot from the one-year Manchester course to train as a Teacher of the Deaf, I was keen to get going.

The pupils were all profoundly deaf. They all wore body-worn hearing aids in harnesses on their chest – some had one hearing aid with a lead to each ear, then gradually they were all given two aids. It was obvious that they did not like wearing them, and they disliked the group hearing aids even more, with headphones that were plugged into their desk so they could not move away from their seat, and microphones that they were expected to turn on when they spoke and off again when they had finished – and these children were aged eight. As a teacher, my role was to insist that amplification, either their individual aids or the group aid, was worn at all times except of course for swimming and for some outside sports. The amplification was seen as a key to the development of their spoken language and their reading and writing, although it was clear that they could hear very little, if anything, even with their powerful hearing aids.

A lot of the teaching was done at a ‘whole class’ level. There were eight children in my first class, with more girls than boys, which was unusual as there were more boys in the school. A typical language/literacy lesson comprised me presenting a story or some nonfictional information, aided by pictures, and then the children were expected to write, copying from either the blackboard or the overhead projector. They might be expected to insert the correct word in a blank space in a passage, to put the words of a given sentence into the correct order or to put sentences into the correct order to retell the story. Copying was slow and laborious and the children made frequent mistakes. They were, of course, copying without being able to rehearse what they needed to copy by repeating it to themselves as they were copying language that was beyond their own level of language development. The hope was that by copying it they would learn the language, both the vocabulary and the structures.

Whilst the children were busy copying from the board and drawing pictures to illustrate, I would hear them read individually. They were usually keen to come and read. On the whole they found nouns and verbs relatively easy, although they might only give the verb root (eg skip for skipping or skipped). The rest of the sentence was more challenging. My role was to check their pronunciation (and get them to repeat the word until it was the closest they could produce to the target); to check their understanding of individual words and to ensure that they did not omit any words that they might not have noticed (typically to ensure they read ‘he went for a walk’ and not simply ‘he went walk’, for example). I stopped them so frequently that they never developed a flow of reading and rarely would they read a whole page of print, which might only be one sentence, without me stopping them. I tried to find books where the story was obvious from the pictures, but already the difference between their level of language and that of the books meant that if I chose books with an appropriate language level they would turn their noses up and tell me they were not a baby! The alternative was to select books that were more at their level of interest and then modify the text. This was achieved by using sticky labels to stick over the original text on which I would write a simplified version. Their reading did improve, but the rate of progress was not as fast as I hoped.

Learning to write was perhaps more challenging for the children than learning to read. One approach was for me to present a story using a picture sequence. We would then discuss the story and I might write up a single word or phrase that the children might use in conjunction with each picture. The use of a picture sequence provided some basic structure and they could usually produce a piece of writing to retell the story, even if the English was very ‘nonstandard’. However, I was also expected to encourage the children to write something unaided. This was often attempted on a Monday morning and the children were expected to write their news from the weekend. This did not meet with much enthusiasm from them or from me! The children adopted different tactics when confronted with this task – a couple went so slowly that they wrote very little, but another approach was to write several sentences along these lines:

I went shop mummy

I went swim

Ice cream

I went grandma house

This at least gave me something to work with, but it was very frustrating for me that they produced the same errors again and again. Out came my red pen and each sentence was corrected. The following week they would produce something very similar and I would correct it again. Overall it was a rather punitive approach to the children as if it were their fault that they did not make more progress, when in reality they were doing their best and my skills were limited.

On the whole I enjoyed my time at Whitebrook. It was a supportive environment in which to learn more about deafness and deaf education and it was good to work with small groups of children and be encouraged to take them out and give them a wide range of experiences, but I gradually became more and more frustrated by their slow progress and my inability to help them further. I went and trained as an audiologist and decided to become involved in working with very young deaf babies and their families. My whole approach to teaching literacy evolved too as I began to see and value what each child was able to bring to the process – how they can bring their own understanding to reading a book and so make meaning from it and also how they can engage in writing. I was pleased, over the course of my career, to be a part of this changing approach to literacy. Of course some deaf pupils still struggle with literacy, but many more of them are able to gain an adequate level of reading and writing, and even to enjoy it!

When I started working as a Teacher of the Deaf in Leeds, the first truly bilingual provision in the UK, I was full of excitement about language and literacy learning and teaching. With a Modern Foreign Languages degree and PGCE in my back pocket, experience of teaching English as a Foreign Language abroad and then French in UK secondary schools to forbearing teenagers, I was brimming with ideas about how we might approach the development of language and literacy skills with deaf learners. I had experienced the thrill of language teaching and learning and witnessing those connections being made in my own, as well as my students’, minds between new worlds of meaning.

I worked with a Foreign Language approach from the start. It had been my training and this had been rigorous. I had learnt as an MFL teacher to carefully plan, structure and scaffold language learning and language use in the classroom and to combine explicit teaching of grammar with the communicative experience of language in use. You do not expect foreign language learners to ‘catch’ language in the way that most first language learners do, you have to set up the conditions. This made sense to me in the context of deaf education and in a bilingual environment where British Sign Language was one of the teaching resources, everything seemed possible.

The challenge of teaching reading for me was all about the development of learner strategies and curiosity. I sought to teach my pupils the skills to interrogate text and extract meaning from it, and at the same time to ‘notice’ how written language was structured. To do this you had to instil the wish and desire to discover the text and find the meaning within and, of course, we could do that by bringing texts to life with BSL stories. In an environment where exploring the new and unknown was safe you could then present challenging texts to pupils but with very specific learning goals such as scanning for key words or skimming for the gist. This approach, once called ‘Directed Activities Related to Text’ (DARTs), along with a good dose of the MFL diet of vocabulary and phrase books gave learners a sense of empowerment and ownership over their reading activities and an expectation that text held something for them and they could discover it. I found it thrilling to see learners find patterns in written language, share roots and shapes of words and to enjoy the problem-solving approach to reading activities and the accomplishment of ‘cracking the code’. Because we prepared and planned these activities in BSL, in one way or another, the connections with meaning came easily and a curiosity about how meanings could be differently expressed in sign and written language developed.

At that time, I was cautious about incorporating the use of phonological skills, but I had read the research that suggested the potential for phonological awareness, and it encouraged high expectations in this regard. I felt that the bilingual environment that we had developed provided the support and contingency to develop challenge in terms of developing the learner’s connections between the spoken and the written word and that this connection could only help them. We began to read books aloud to the pupils within the menu of BSL preparation and support, and DARTs activities. All of this took place within a topic-based primary curriculum at that time so that there was a coherence of focus on language and content objectives across all of the learning activities in the mainstream and small group settings.

Even at this time, when we did not have the state-of-the-art hearing technologies that we have now, or the improved acoustic environments and sound field systems, I felt that working bilingually, with expert deaf colleagues, meant that we could push and stretch the learners in terms of the development and use of their sign, spoken and written language resources as well as their language learning strategies and language awareness. I still find it hard to accept any approach that only makes use of a fraction of the resources or repertoire available to the learners and I struggle to comprehend a contemporary bilingual setting (such as described in the US) that does not exploit, where possible, the use of auditory and phonological skills alongside the skilled use of BSL and text along with other semiotic resources that we habitually assemble in the classroom context. I know that it is a complex business and it takes really careful planning and choreography to work with languages in this dynamic and flexible way but for me it is a gift of a job that provides insights into the very processes of learning.

As a researcher I’ve been lucky to be able to continue my exploration of reading development. The work that I did with Linda Watson with deaf and hearing parents and the different ways in which they shared books in the home setting was a very humbling project as we saw how different parents assembled and deployed the sign and spoken language resources available to them to share much loved stories and books with their young deaf children.

I’ve also really enjoyed working with teachers to help them set up action research projects in their schools to develop shared reading projects, assessment protocols and creative writing approaches.

My appreciation of deaf learners’ potential for language and literacy learning continues to develop as I observe deaf children and young people from bi and multilingual homes navigate one or two written languages in their lives. I believed as a new ToD in the 1980s and still now as a ‘seasoned’ teacher trainer that if we look carefully at the language resources available to each learner and the potential therein, and we apply a creative but rigorous and truly bilingual approach that anything is possible.

In 1868 Charles Dickens published a little-known novelette entitled ‘Dr Marigold’ where the education of a deaf beggar girl exceeded all expectations. The moral of this brief tale seemed to be that achievement was more likely to occur when high aspirations were motivated by mutual respect and understanding between teacher and child. My own experience of teaching deaf children validated that premise.

In the tale, Sophy was a beggar girl who was adopted by Dr Marigold, a tinker who taught her to read and write, an achievement rare for these times. The tinker was unlikely to have had much education himself and was certainly not qualified to teach, yet somehow he cultivated a relationship with the child that empowered her to be active in her own learning. This instinctive interaction is at the core of true teaching and learning (of ‘educere’ (to lead out) rather than ‘educare’ (to train or mould)) when it is effective enough to form the basis of social and cultural advancement for the child.

At the point where Dr Marigold felt unable to take Sophy’s progress any further he was determined that she should continue to learn. To that end he took her to be assessed by the professionals in a ‘Deaf and Dumb Establishment’ in London where, on finding that Sophy could indeed read and write, they exclaimed, “this is most extraordinary”. When asked what he wanted for his daughter Dr Marigold replied: “I want her, Sir, to be cut off from the world as little as can be, considering her deprivations and therefore able to read whatever is wrote with perfect ease and pleasure”.

It is significant that Inclusion and Literacy remain two key issues in the education of deaf children today. The pity is that Dickens didn’t go more deeply into this subject and produce a full novel on the education of a deaf child along the lines of Oliver Twist and David Copperfield. If he had done so, a deeper understanding of the issues facing deaf children in terms of literacy and social inclusion may have been secured and developments to address them may then have gone much further down the line than they are now.

Fast forward just over a hundred years to 1979 when, quite unaware then of Dickens’ brief illumination of the way forward, I met my own ‘Sophy’. Not in the singular but in the form of nine prelingually and profoundly deaf children in a school in Liverpool. I was a fully qualified teacher with a B. Ed from Liverpool University, but not yet qualified to teach deaf children though studying for my BATOD Diploma as a useful way to learn the theory alongside the practice of specialist teaching.

So there I stood before my first class, a willing but uncertain young deaf teacher with no sure idea of where or how best to start. Thus began, by trial and error, a pathway to a mutual understanding, which enabled both teacher and children to learn from one another. It was by this process that these children taught me how to teach. Not by creating a teacher-dominant environment in the classroom, but by acting as a facilitator to learning.

Lest it be presumed that I would have a natural empathy with the children because we shared the same disability – that was not the case. There is a vast difference between those who were born deaf and those who lost their hearing after the acquisition of speech and language as I did when I was treated with streptomycin for TB meningitis at the age of seven. In fact, the children were initially suspicious about me actually being deaf because I could speak very well. After ‘testing’ me in all sorts of ways and realizing that I was indeed deaf, just like them, they were delighted. They had never believed a deaf teacher to be possible and our empathy and rapport came from our willingness to learn together.

The immediate problems were twofold: first, I was unable to communicate with them effectively because I was not born deaf and I did not know sign language. Secondly, I had no idea how intelligible and meaningful speech was acquired without experience of clear sound because that is the way I became literate. Much less was I able to understand how the lack of sound could be overcome when encoding and decoding a language such as English with so many exceptions to the rules of grammar. How did they think? Was it with a few words or pictures or a mixture of both? These pupils I was responsible for did not have the benefits I had had from having once experienced perfect sound. Unlike me they could not use tools like phonics to guess at how words were shaped for speech and literacy. The first priority was soon obvious. I had to work on establishing a clear line of communication with these children before either my class or myself could learn anything at all.

The school in Liverpool had an oral/aural policy which I respected until I found the pupils were struggling with it. Formal assessments showed their standards of reading and writing were very low yet they were clearly intelligent and lively children with wide interests. After watching them ‘talk’ to each other so vibrantly with their faces and their hands then turn to me and stiffly make what use they could of the little English they knew I decided I had to learn their language first to be on a par with them. Basically, I did a deal with them. I asked them to teach me their language and I would teach them mine. And that’s when the fun began.

Yet, even within an increasingly clear and enriched communication environment it is almost impossible for me to convey how I taught reading and writing to deaf children to the standard they required to pass CSE English at the age of sixteen. They were the first ever in that school to do so. The reason is simply due to the fact that there is no one right method that can be singled out as a perfect route to literacy. Each child is different with distinct learning needs that have to be met.

I believe it is the teacher’s responsibility to keep an open mind; to develop a flexible and wide range of communicative expertise; to take their cue from the pupils as to how best to meet these needs if they are not making progress by the oral/aural method of communication alone. Another essential is to be highly proficient in the teaching of English. When assessing their levels in reading and writing we try to work out the best way to take them forward by making reading and writing linked and mutually reinforceable. It took me many years to hone my expertise and it was easier to demonstrate this to student teachers later by allowing them to observe me teach. During one session a student teacher asked me why I had explained the same thing differently to two pupils sitting next to each other. I was not even aware I had made the adaptation. I even found it hard to explain why I differentiated between these two pupils. It was an instinctive reaction, familiar, I believe, to those with a natural vocation to teach.

Respect for the children is fundamental. The control of my developing sign language was in their hands. The respect this gave them empowered them and motivated them to work equally hard on English. But first, the damage done to their confidence had to be jettisoned. For literacy skills to flourish I did not insist on good speech or indeed any speech at all that they found hard to use. Nor did I ever attempt to correct their reading as part of a speech lesson, which was a common approach at that time and imposed a double dose of inhibitions on the child that obviated any chance of gaining pleasure from reading. Instead the focus was placed on reading for meaning by allowing the pupils to read passages as a whole in their own time then explain what meaning they had accrued from that reading. From that I was able to determine their level of understanding of the text and what was identified as the difficulties we would have to work on.

Although the standards of reading and writing were both low the hardest thing to eradicate was an almost total lack of confidence in the skill of written English. Their vocabulary was limited and their grammar non-existent. They would write a single word and look up for approval and repeat the same process ad infinitum. This focus on a single word at a time prevented them acquiring the gestalt, the pattern of words and how they grouped together to convey meaning. I had to break this fear.

What facilitated this was the way I reacted to the pupil’s corrections of my own fledgling signing. I laughed, thanked them and tried again. They laughed with me. I assured them that making mistakes was normal and that we all learn from our mistakes just as they could see was happening with me. Also, the material I used was what the children gave me of their own concrete experience so that what they wrote about was based on that and on their own interests. The aim was to capture the vibrancy they demonstrated when talking to each other, and increasingly used with me too. They were encouraged to transfer it to paper in any way they wanted with words, drawings, cartoons anything that produced a flow and no corrections were ever made until they got the idea of writing in an uninhibited flow.

The problem with that was the flow often became a flood as some of the pupils began to think that quantity was better than quality and this had to be gently curbed by introducing systems like the Fitzgerald Key (a colour coded system encouraging deaf children to construct sentences that were grammatically correct. Cards were laid out to set the sentence structure – Subject (who); Verb; Object (what, where). Extra categories could be added as appropriate e.g. adjectives and adverbs. to ensure a subject-verb-object basic structure.) English then began to be taught like a foreign language, using sign language so they could see where the differences lay. They were encouraged to maintain their own dictionary of new words by using a suitable dictionary and were tested on spelling these each week. When the structure of a sentence was established attention turned to grammar. Conjunctions came in to link two sentences into a longer sentence. Adjectives and adverbs were exploited to enrich the quality of the writing; paragraphs as a way of cutting up the flow started to be used for both chronological and debate-type essays and then each child began to develop their own style of writing as could be seen from their diary writing that was never marked as it was evidence of the written language skills that they had and had not mastered which indicated the next set of objectives for each child.

Corrections were introduced when the pupils were confident enough to see that they were helpful. The basis of correction was to address only one aspect of the child’s writing at a time. It depended on what element of each child’s writing would, if corrected, improve the quality of the writing as a whole. As every child was at a different stage there were regular sessions for the self-correction of written work along with group corrections on comprehension questions set on each chapter of the shared book so that the learning process could be shared in a supportive manner.

Individual reading was encouraged but the daily group reading sessions formed the core of teaching reading and writing formally so that the two were firmly linked and mutually reinforced. The selection of books was based on what the children were interested in as a group and/or the use of classics written at different levels of difficulty. I produced my own simplified versions of such books when necessary. Whenever possible, we watched a subtitled film of the book or went to see a play in the theatre in advance so that when they read it they would understand the flow of the story and the context of the characters within it and thereby manage to look closer at the details in that context.

Let me be clear – I am writing from my own personal experience as a teacher. I do not advocate any one form of communication over another. All methods are relevant and their use should be determined solely in response to the needs of the child, not the policy of the school. Criteria used to determine progress in literacy, including the National Curriculum Targets of Attainment, provide the evidence that the approach to any individual child is successful or not as the case might be and responses made accordingly.

Those deaf people who found learning through the oral/aural system suited them were in the correct placement. Having said that, in my case, it was not the policy that gave me speech and language as I had already acquired such skills before I lost my hearing. What I most benefited from was having a deaf peer group in small classes and good visibility for lipreading. The children I taught for over a period of 34 years could not benefit from the same approach but they succeeded in spades when the right method for them was applied. In addition, as their literacy skills increased, so too did the intelligibility of their speech because English had become more meaningful to them.

At the end of the day, employment opportunities, independence and social integration are the achievements of literacy and that is what will determine a deaf child’s future, not so much the quality of their speech. It is our individual and collective responsibility as teachers to make sure this happens. Let Dickens point the way.